A year ago, an annual FB post was noticed by the DW. I’d not yet read Pam’s book but her request to share my story has scratched at the back of my brain ever since. After reading Death Becomes Us, I knew I could trust her and her audience with my story. As this is a particularly meaningful year for me, it felt like the time was right.

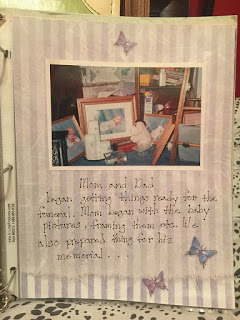

My son, Christopher, was born by emergency C-section 16 years ago, today. He was 4 weeks early. We found out later that I’d gotten a group B strep infection earlier than they tested for and it had killed the placenta. The entire experience was traumatic, in ways that have haunted my nightmares ever since, but I’m not going to relate that here. Suffice it to say that it was an abusive marriage and had been an equally brutal pregnancy. I was alone in every way that matters and everything went wrong. But in the end, Christopher was alive and recovering, or so we thought.

Preemies must prove that they are eating and growing at a certain rate before a hospital releases them so, for two weeks, we believed we had a normal kid that had just gotten a rough start. A midnight life-fight to Primary Children’s hospital changed all that. Did you know you have to promise that you won’t freak out if your kid flat-lines mid-flight to ride with them? With only minutes to absorb the situation, I had to admit that I didn’t know if I could stay calm. They flew off without me.

My husband (at the time) gathered our things from the hospital sleep-room (a temporary room provided to parents with children who’ve been hospitalized) and drove us the hour and a half to where our son had been taken. What followed was five and a half months of fighting for Christopher’s life.

It turned out that when the Group B Step had overwhelmed the placenta and killed it, Christopher had been deprived of oxygen. We were able to save all his other organs that had been affected but in the end his kidneys were destroyed. They only do transplants with adult kidneys so the minimum weight required for surgery is 25 lbs. Healthy babies gain that in the first three months, sometimes less. After five and a half months we estimate that Christopher had gained between 8 and 10 pounds. They estimated he’d be 2 years old before it would be possible and they didn’t expect him to live that long.

When we signed the DNR that March he’d been diagnosed with meningitis for the 3rd time. It’s important to know that there are 3 kinds of meningitis, but most people only know about the worst one, the one that kills healthy adults in days. That’s what our already medically fragile, underweight, and immune compromised infant contracted. You also need to know that, excluding surgeries, they don’t give babies pain killers. That poor kid was practically tortured, for months, by our efforts to save him. If I could go back and change one thing, I would give him pain killers.

So when we decided to stop fighting, painkillers were the first thing he got. The poor kid slept for a week. We were shocked. And then we were sent home from the hospital for the last time. It was terrifying. We had no idea what was going to happen or what his death would be like. Hospice care was scheduled. They hurriedly dropped off the equipment and scheduled a follow up to prepare us for what came next. He didn’t make it to the second appointment.

My baby boy died in my arms at 11:30 pm of April, 11th, six months and one day after he was born.

A call was made to the funeral home that had been arranged by family. I held his body for another half hour as we waited for them to arrive. I was surprised when a man with a white van was all that showed up. He explained that they didn’t really have a stretcher or blankets for babies so we left him in the pajamas and blanket he’d died in. Then I calmly carried my son’s body out to the van. The short walk defied time and space, slipping into one of those forever moments that you can’t forget. A single thought echoed in my head with each step. It said, “ This is the last time you will hold him so remember every second.”

I placed his body on the front seat as instructed. It funny how you think about the need for buckles and safety belts and then have to remind yourself that they don’t matter anymore. I covered his face with the blanket and an ache began in my arms. It turned out to be an emptiness that has persisted to this day.

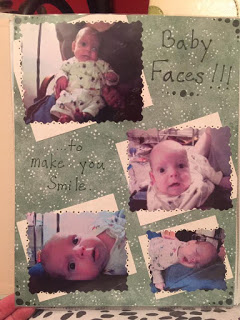

The van door closed and the husband, who had never wanted a child, guided me back inside as it drove away. The funeral was a rare 5 days after his death, due in part to the fact that even though we had known it was coming I had refused to do any planning. I figured I had a lifetime left to deal with his death but only days to enjoy what was left of his life. I wasn’t going to stain those days with plans for it to end.

I decided on a viewing and a graveside service only. The caskets they offer for infants were little more than overpriced plastic shells and hideous ones at that. So his father made him one out of pine, staining the wood to look like it was cherry and lining the inside with padding and white satin.

I went to Baby GAP and got him clothes. I chose a white sleeper that buttoned up and got it a couple sizes larger because they told me that his body would be stiff and hard to dress. I then found a sleeping cap, socks, and booties to match. The rest of the funeral I planned and organized, making all of the arrangements and printing the programs myself.

For his viewing we invited friends and family to write letters or notes to him that were put in a matching wood box and buried with him. A friend asked if she could take pictures, promising that they would help later. She was right. And it’s something I advocate to this day. For me it is a constant reminder that his body is finally at peace, something he almost never experienced in life. And oddly, since the embalming fluid used is pink, he looks healthier in death than he ever did in life.

There are things we did at and surrounding his funeral that I later learned are really helpful for healing but at the time I was acting on pure instinct. I felt especially responsible to watch over his body until it was safely buried. I think that’s why, at the end of the service, we stayed to finish it.

Once everyone had left I tucked a stuffed animal, one that had been with him during every hospital stay, under his stiff arm and kissed him one last time before the casket was nailed shut. Those nails might as well have been going through me. My husband and I lowered his casket into the cement vault after he removed the handles we’d been told wouldn’t fit. (He’d used chrome towel racks, the ones usually meant for bathrooms, as the handles and I later found out that he returned them to the store. It’s weird to me to think that those ended up in a stranger’s house.)

The box with everyone’s letters and rose petals were placed in the cement vault with his casket before the cap was lowered. The workers expected us to leave but I asked for a shovel. They produced two and we began to fill in the hole. When they realized we weren’t moving aside to let the tractor finish they picked up more shovels and helped us finish. I finally stood back when they brought out a machine to tamp down the remaining mound. Fresh sod was laid and just like that, the ground appeared to have never been disturbed.

We couldn’t afford a head stone so I had prepared two shepherds crooks. I hung a set of wind chimes on one side and a candle lantern on the other. A handmade wooden plaque on a chain held the two crooks together and was the only marker. Later it would be stolen by vandals that thought anything left in a graveyard was free game and the city would pass a law that only allows stone markers. So now, only a plain, uncut, unfinished, granite stone marks his grave; placed there by his father during a manic episode that had taken him up one of the nearby canyons. Someday I will save enough to put the stone bench there that I dream about, one with a little cherub on one side, waiting for someone to talk to.

The saddest part to me has come in the aftermath. You see, when adults die, we do our best to remember them for their life. Sure, it’s our way of fending off the pain but it’s an important coping tool for their family as well. When a baby dies, that’s all people hear. The idea of the pain of such a loss obliterates any opportunity to remember the good times. You learn not to talk about your child beyond the basic facts, because nothing that was good about his life could overshadow the tragedy, he died, and nobody wants to hear about a dead baby.

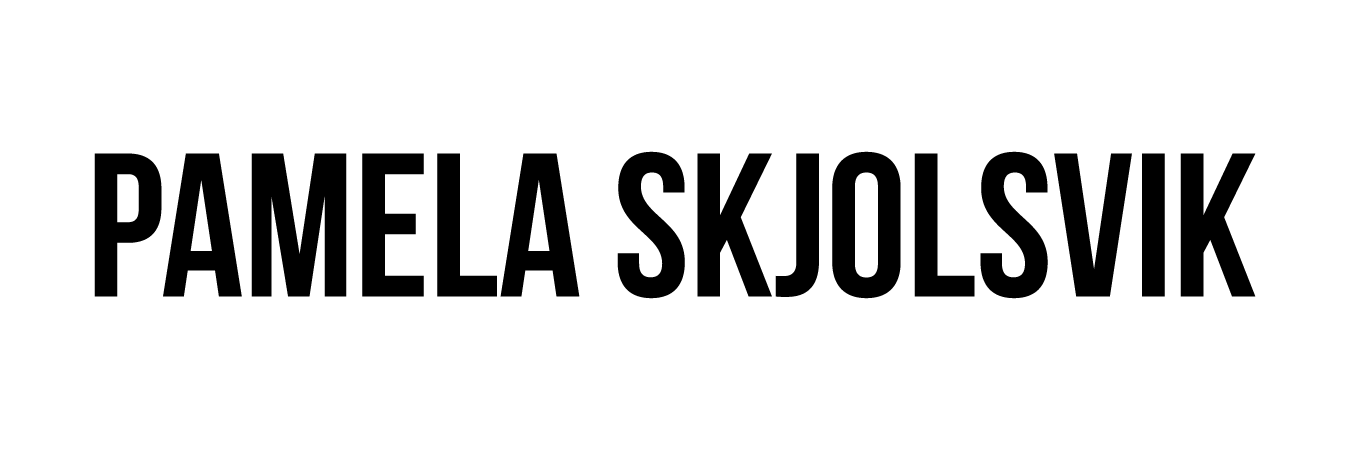

The reality is, my son was astounding, not just for what he endured but for what he evoked in others. In his first month of life he brought people into the same room whose hatred and loathing had divided families for over a decade. Members of the family I’d been cut off from since my marriage came back in full force and so many walls came down between people. Friendships were born that I treasure to this day. Specialized nurses changed their shifts to care for him, an RV was lent to us by a company so I could stay at the hospital with him, and in the end he didn’t die until everyone had had a chance to say goodbye. There were hundreds of precious, beautiful, and even funny moments. But I never get to tell those parts of the story, because things change around you after your baby dies.

Suddenly no one who knew wanted me to hold their baby or touch their children, as if I was somehow bad luck. The silent ache in my arms grew. 16 years later and I still worry about new mothers finding out, because when they do, they get that same look on their face; a mixture of pity and fear. The friends that have let me hold their babies will never understand the gift they gave me.

But if they read this perhaps they will understand better why, except for two days of every year, my life goes on as if I’m completely fine with losing him. And then, on the day he was born, and the day he died, my life stops. I don’t work. I don’t make plans. I let those days be whatever they need to be. Some years they are no big deal and some I relive every moment like its happening all over again.

And this year he would be 16. How am I old enough to have a 16 year old? I divorced Christopher’s father a few years later and he in turn disowned his son. It was a blessing that we’d never had any more kids together but when I married again the plan was always to have more kids. That’s one of the questions I’m always asked. Do I want more kids? Can I have them? There is no medical explanation for why they’ve never come. Even adoption has eluded us, though not for lack of trying. So much of other people’s lives are measured by what their kids are doing. Not having kids sometimes feels like living outside of normal time. But if I’m only ever going to have one kid, I’m glad it was him.

So what do you say to someone like me? Its easier than you think but probably the safest question is: what do you wish you could tell people about your kid? Or how about: what’s your favorite memory? What’s the funniest thing he did? Ask us questions like we are ordinary parents, ordinary people, that want to share the best of our memories.

Everyone says this stuff gets easier with time but if you’re counting, I’ve barely allowed myself more than 32 days, just over a month, to feel the pain as deeply as it asks to be felt. I hope that someday the world makes a place, makes it acceptable to grieve for as long as is needed. Until then, I don’t know what else to do but let it tear me apart, put it away for six months, then open the box and see what is next for me to work through in a day, before I put it away again and go back to my life.

Jennie lives happily with her husband and their 2 dogs in Portland, Oregon. She is an award winning poet, a published author and an editor with her own business, Myth Machine ePublishing where she helps other writers prepare for the publishing process. They travel every chance they get and love new adventures.

Thank you so much, Jennie, for sharing Christopher with my readers. Grief can be isolating, so it is my sincere hope that someone out there will feel less alone by hearing your story.